Aug 31 2015

If Europe emphasises exploration and conquest, China relies on its Confucian heritage of consolidation of power, much like its ancient boardgame, weiqi

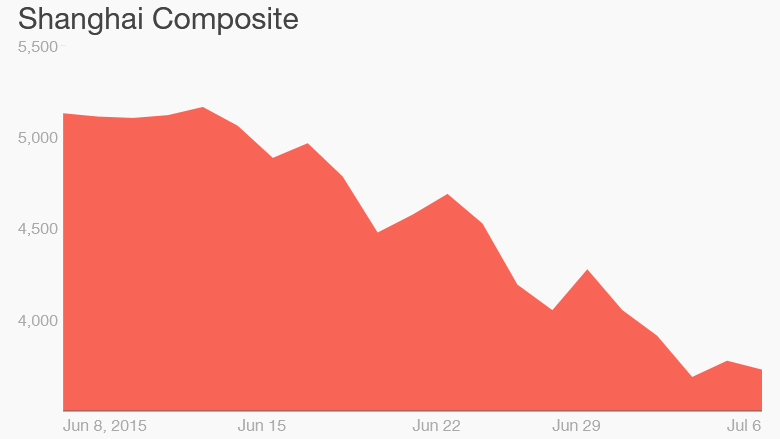

Experts view the recent turmoil in the Chinese stock market as a consequence of the overcapacity of the Chinese infrastructure, misallocation of resources, and the ballooning of internal debt. The steps taken by the Chinese government to deal with this crisis appear to be half-steps. On the one hand, it has promised more transparency in the financial sector so that the valuation of the offerings is reliable; on the other hand, it devalued its currency and has kept it pegged low compared with other currencies.

We see similar half-steps in its diplomatic relations and the projection of its economic power. Although China proclaims its desire to have good relations with its neighbours, it is aggressively pursuing unilateral action on the disputes regarding the control of the Paracel and the Spratly islands in the South China Sea. After constructing a string of artificial islands, it is building deep-water ports, military-grade airstrips and strategic infrastructure to the alarm of its neighbours and the United States.

China’s greatest trading partner is the US, so one would imagine it would generally be sympathetic to the US position in international conflicts. But WikiLeaks shows that while China presents a façade of being reasonable and responsible in its actions, it is actively supporting American adversaries in various theatres, and has supplied nuclear and missile technology to Pakistan and North Korea. Is there a deeper consistency to China’s actions?

I would like to argue that difference in the international dealings of US and China are a consequence of their different cultural styles. These styles get expressed not only at playfields but also in business, diplomacy and war. The Chinese style is based fundamentally on its Confucian heritage with its emphasis on study, ceremony, loyalty and harmony. This style is best represented by the Chinese boardgame weiqi, better known in the west by its Japanese name go.

Weiqi is played by two players who alternately place black and white stones on vacant intersections of a grid of 19×19 lines. Once placed on the board, stones cannot be moved unless surrounded and captured by the opponent’s stones. This is a game of controlling territory and the object is to surround a larger portion of the board than the opponent. Groups of stones must have at least two open points to avoid capture and, therefore, placing them close together helps them support each other. Stones far apart create influence across more of the board and help occupy more territory. The strategic challenge of the game is to find a balance between conflicting interests of staying close for safety and going far to capture territory. It is the perfect game to learn imperial strategy.

In contrast, the game that captures the way the west sees its sports and war is chess in which the players perform tactical manouvres to attain winning material advantage or to mount a successful attack on the king. This can involve real sacrifice for the sake of victory. Although primarily tactical, the game does have strategic elements that involve piece mobility, centre control and pawn structure. The chess player manouvres to force and consolidate a winning material advantage. The history of the west is about exploration and conquest. It has celebrated clear resolve and victory as in Caesar’s famous proclamation: “Aleaiactaest,” or “the die is cast” when he crossed the Rubicon.

The Qianlong emperor and Macartney

For many centuries, China had little intercourse with other countries but after trade began European nations found their commercial relationships with China to be unsatisfactory. For the English, viewed as a nation of shopkeepers and traders by Adam Smith, trade was the key to their power and prosperity. In the 1790s, the British government of William Pitt the Younger wished to consolidate its power in India by cutting through the restrictions of the Canton trading system imposed by the Qianlong government on European merchants in 1760. George Macartney, colonial administrator of Madras and a diplomat, was chosen as British envoy to the Qing empire.

Once in China, Macartney refused to kowtow and finally it was negotiated with the Chinese legatee that he could go down on one knee. The meeting went smoothly but Macartney was never able to negotiate business with the emperor or his representatives. In fact, he was told to leave.

As Macartney’s embassy was leaving, he was given a reply from the Chinese emperor for King George III. In this, amongst other matters, he was criticised for not following the court protocol: “I do not forget the lonely remoteness of your island, cut off from the world by intervening wastes of sea, nor do I overlook your excusable ignorance of the usages of Our Celestial Empire.”

The emperor followed this by expressly denying the requests to open various ports to British ships, permission to establish a warehouse in Beijing, small island near Chusan for a warehouse, a site in the vicinity of Canton for the navy, and permission to proselytise. With regard to permission to spread Christianity, the emperor added that the jesuits “in my capital are forbidden to hold intercourse with Chinese subjects; they are restricted within the limits of their appointed residences, and may not go about propagating their religion. The distinction between Chinese and barbarian is most strict and your ambassador’s request that barbarians shall be given full liberty to disseminate their religion is utterly unreasonable.”

The failure of the Macartney mission was determined by conflicting cosmologies of China and Europe. In his memoirs, Macartney wrote about the poor quality of life for the Chinese under Qing rule. He realised that the Qing state faced fundamental structural problems. He wrote: “The government, as it stands, is properly the tyranny of a handful of Tatars (Manchu) over more than three hundred millions of Chinese.”

He also foresaw a serious internal challenge to the power of the Qing in China: “The frequent insurrections in the distant provinces are ambiguous oracles of the real sentiments of the people. The predominance of the Tartars and the emperor’s partiality for them are the common subjects of conversation among the Chinese whenever they meet together in private. There are certain mysterious societies in every province, who, though narrowly watched by the government, find means to elude its vigilance, and often hold secret assemblies, where they revive the memory of ancient independence, brood over recent injuries, and meditate revenge.” The Taiping, Nien, and the Boxer rebellions were to follow in the next several decades and the last Qing emperor abdicated in 1912.

Weiqi and the strategy of a thousand cuts

If we see the encounter between China and Macartney through the lens of weiqi, England was a small country in a faraway place that did not deserve any investment of the court’s energy. Modern China may be viewed as a restoration of the Qing empire, with the difference that the court has been replaced by the Communist Party.

Weiqi is profoundly strategic, but with incisive and complex tactics. The game proceeds with the players trying to balance conflicting and yet complementary objectives of territorial acquisition, projecting “influence,” maintaining access to the centre, and attack and defence. The tactics used in the game involve diversions and pincer and broader attacks and sacrifices. In weiqi, the consolidation of territorial borders takes place between safe opposing armies.

If chess is about decisive victory by vanquishing the enemy by taking the fight to the place where the king is located, weiqi is about consolidation of territory. This is the reason that the Qing emperors were busy fighting to keep the empire together, rather than advancing it elsewhere.

If Europe emphasises conquest, for China, the Middle Kingdom, the focus is on consolidation of its power. This difference between the styles of chess and weiqi explains Chinese history and why the Chinese did not go out to explore and conquer other nations. Another aspect of weiqi is a relentless pursuit of strategic gain, which may be called lingchi, or the strategy of a thousand cuts. The term lingchi derives from the notion of ascending a mountain slowly, where one requires a thousand small steps to reach the top.

Beijing’s warnings on economic consequences for those who challenge its political orthodoxies are consistent with the weiqi style. The punishment to those who don’t heed the warning comes in a thousand forms. China’s relentless pressure on Taiwan for reunification in fulfillment of its imperial vision is not only in terms of missiles fired across it on multiple occasions but constant shrinkage of its diplomatic space. The Chinese dole out punishment to those who welcome the Dalai Lama. Even Barack Obama met him not in his office or in public but in the basement, and the Lama had to leave through the backdoor of the White House.

(Subhash Kak is a Regents professor of engineering at Oklahoma State

University and author of 20 books, including The Architecture of Knowledge)

Related Posts

- 76Using a universally relevant metaphor, Zbigniew Brzezinski, former National Security Adviser to US president Jimmy Carter, wrote in The Grand Chessboard (1997): "Eurasia is the chessboard on which the struggle for global primacy continues to be played." China's New Silk Road strategy certainly integrates the importance of Eurasia but it…

- 71Alexander Vurving from the Honolulu-based Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies takes the Chinese board game of weiqi or Go to describe the country's grand strategy in the disputed South China Sea in an article written for the website of National Interest magazine on Dec. 8. Vurving said that while…

- 61In May, 1997, I.B.M.’s Deep Blue supercomputer prevailed over Garry Kasparov in a series of six chess games, becoming the first computer to defeat a world-champion chess player. Two months later, the Times offered machines another challenge on behalf of a wounded humanity: the two-thousand-year-old Chinese board game wei qi,…

- 49Orginal post is here : http://thediplomat.com/2014/12/maritime-southeast-asia-a-game-of-go/ Over at The National Interest last week, Asia-Pacific Center professor Alexander Vuving ran a nifty longish essay explaining China’s grand strategy in the South China Sea in terms of the Japanese game Go, or weiqi as the Chinese call it. It’s well worth your time.…

- 39In Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), the super computer HAL easily checkmates astronaut Frank Poole. In real life, the victory of machine over man came true in 1997, when Deep Blue defeated chess world champion Garry Kasparov. But unlike in chess, where computers can vanquish even the best…