David Dredge of global hedge fund Fortress has built a career studying, predicting and protecting against the world’s major financial crises. The recent convulsions in global sharemarkets are “just the beginning” of a painful adjustment as money drains from the emerging market economies, he says.

“August 2015 will go down in the record books, much like July 2007 or July 1997, as the beginning of the coming contractionary cycle,” says Dredge who is the co-chief investment officer of Fortress Convex Asia Fund.

August 2015 will go down in the record books, much like July 2007 or July 1997, as the beginning of the coming contractionary cycle.

David Dredge, Fortress

He’s a believer that markets move in long cycles, which “despite all efforts to the contrary, central bankers have not by any means gotten anywhere close to eliminating”.

Hedge fund Fortress says all emerging economies are in the midst of a painful adjustment after a “burst of credit expansion”. Photo: AP

Hedge fund Fortress says all emerging economies are in the midst of a painful adjustment after a “burst of credit expansion”. Photo: AP

“Like weathermen have not eliminated seasons,” he says.

Singapore-based Dredge says the current volatility in financial markets is in the early stage as markets react to a correction of global imbalances that will last from18 months to three years.

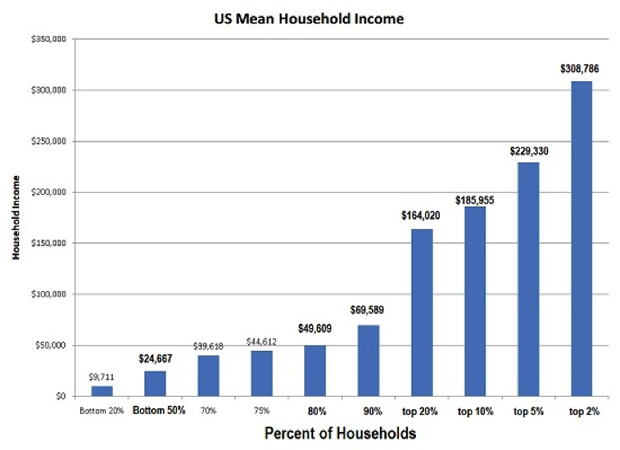

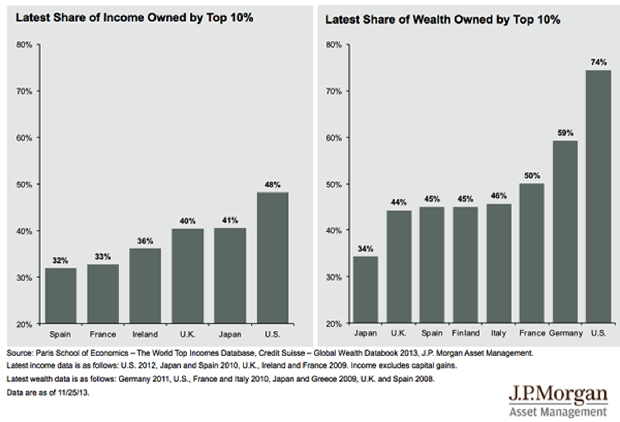

The global economy is made up of nations with a deficit of capital – the West – and those with a surplus of capital – the East and emerging markets, he explains.

Policy determined by deficit

“The flaw is that those with the surplus have all tied their currency to the main protagonist on the deficit side – the US.

“So monetary policy is determined by the deficit of capital side and flows through the currency linkage, and you end up having some form or another of the same monetary policy on both sides, with economies that are 180 degrees diametric to each other.”

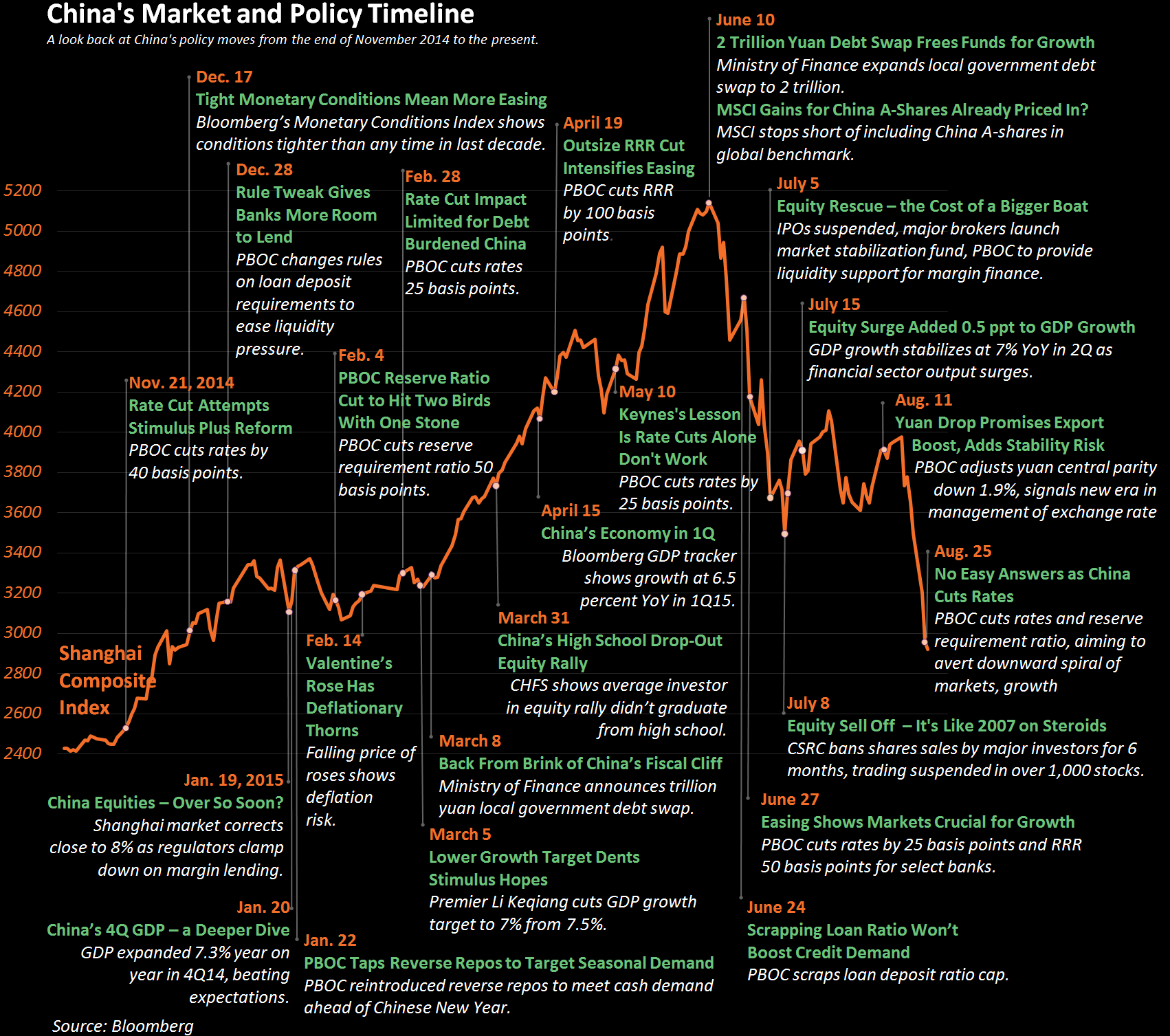

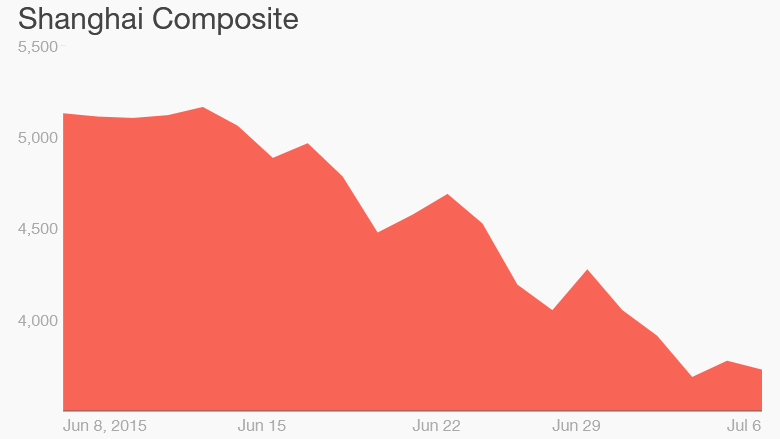

The financial links to easy-money policies in the US have unleashed a burst of credit expansion in emerging markets that has proved unsustainable and is now in the process of unwinding.

That is forcing a painful “market-induced tightening” that will affect the growth of emerging markets as credit expansion is halted and reverses.

The “simplest measure of these imbalances” is foreign exchange reserves, which have swelled in the past few years but are now being liquidated, tightening financial conditions in emerging markets.

“When the hose is on and credit is pouring from the deficit to the surplus side, the FX [foreign exchange] reserves increase and are indicative of the growing size and the location as to where the imbalances exist – because that’s where the most money is going.”

China’s foreign currency reserves peaked at $US4 trillion ($5.7 trillion) in mid-2014 but have since run down to about $US3.6 trillion.

‘In the inverse of imbalance’

“Each crisis occurred at the peak of FX reserves. The emerging-market FX-reserves graph looks exactly like the US debt to GDP because they are just in the inverse of the imbalance.”

Dredge says that differentiating among emerging economies misses the point of what is occurring. Capital is draining from the emerging markets as conditions have tightened, and has been since the “taper tantrum” of May 2013.

“In December 1999 the point wasn’t whether you should invest in Apple or Microsoft. The point was they were both going down [as the tech bubble deflated]. And that’s where we are now.

“The [credit] contraction might be triggered in China with retail margin lending in the equity market, or in Malaysia with recognition of corruption.

“But the trigger is not what we are trying to compare. It’s the potential risk, which is the excess credit creation in the last cycle. In that sense Brazil, China and Malaysia are all the same.”

Dredge co-manages the Convex Asia fund, a “volatility fund”, which manages about $US200 million and seeks to deliver outsized gains in times of market stress.

Stay ahead of spreading fire

He says he’s attempting to stay ahead of the spreading fire and that means looking for cheap exposures to volatility. Interest rate volatility is low and, while foreign currency volatility may have risen, it is below many of the peaks reached over the past five years. Corporate credit spreads, too, are around post-financial crisis lows despite a fair-sized correction in corresponding equities.

“This is indicative that we’re just at the very beginning of this,” Dredge says.

Where does Australia fit in as the cycle turns dark for emerging markets? We’re special in the sense that we have not pegged our currency to the US.

“It is just about the only non-manipulated currency in the entire world, along with New Zealand. By allowing the currency to move and avoid being a hard linkage to the monetary policy whims of the global reserve currency, it takes a lot of the pressure off.”

But there has still been a build-up of risks as credit has grown virtually interrupted and our economic linkages to China make us vulnerable to, not immune from, any shocks.

“Australia came through many of the last several cycles better than most because most of the volatility was allowed to take place in the currency.

“This has allowed the asset volatility to be far less than it otherwise would have been. But that means credit has built up and imbalances, while far less than they would have been, have been allowed to persist.”

Related Posts

- 61Deutsche Bank has fired three currency traders in New York as regulators worldwide ramp up their investigations into potential manipulation of the $5-trillion-a-day foreign exchange market, according to a person briefed on the matter. The three employees include the head of Deutsche Bank’s emerging markets foreign exchange trading desk in…

- 61The move in March by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) to double the RMB’s daily trading band from 1 percent to 2 percent has coincided with a new era of exchange rate volatility. This year, the long running trend of RMB appreciation has reversed course with it losing 3.4 percent against…

- 59The hedge fund industry used to have humble beginnings: in 1990, it had $40 billion in assets under management. Now, its growing appeal has led to a staggering $2.6 trillion in 2013. In retrospect with the mutual funds industry and the global financial markets, this is a small figure. However,…

- 58What is a Hedge Fund? A hedge fund is an aggressively managed investment fund that is maintained by a professional management firm. Hedge funds are typically a portfolio of investments that makes use of advanced and complex investment strategies like short and long positions, leveraged positions, arbitrage, and derivative positions…

- 58Currency traders are having their worst start to a year since 2010 as a dearth of trends in major foreign-exchange markets crushes their investment strategies. Deutsche Bank AG’s Currency Returns Index has dropped 0.3 percent since Dec. 31, dragged down by momentum trading, where investors looks for consistent moves in…

Alexander Vurving from the Honolulu-based Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies takes the Chinese board game of weiqi or Go to describe the country’s grand strategy in the disputed South China Sea in an article written for the website of National Interest magazine on Dec. 8.

Alexander Vurving from the Honolulu-based Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies takes the Chinese board game of weiqi or Go to describe the country’s grand strategy in the disputed South China Sea in an article written for the website of National Interest magazine on Dec. 8.