When stock markets are free-falling 10+% in a matter of days, it’s natural to seek some answers to the question “why now?”

Some are saying it was all the result of high-frequency trading (HFT), while others point to China’s modest devaluation of its currency the renminbi (a.k.a. yuan) as the trigger.

Trying to finger the proximate cause of the mini-crash is an interesting parlor game, but does it really help us identify the trends that will shape markets going forward?

We might do better to look for trends that will eventually drag markets up or down, regardless of HFT, currency revaluations, etc.

Five Interconnected Trends

At the risk of stating the obvious, let’s list the major trends that are already visible.

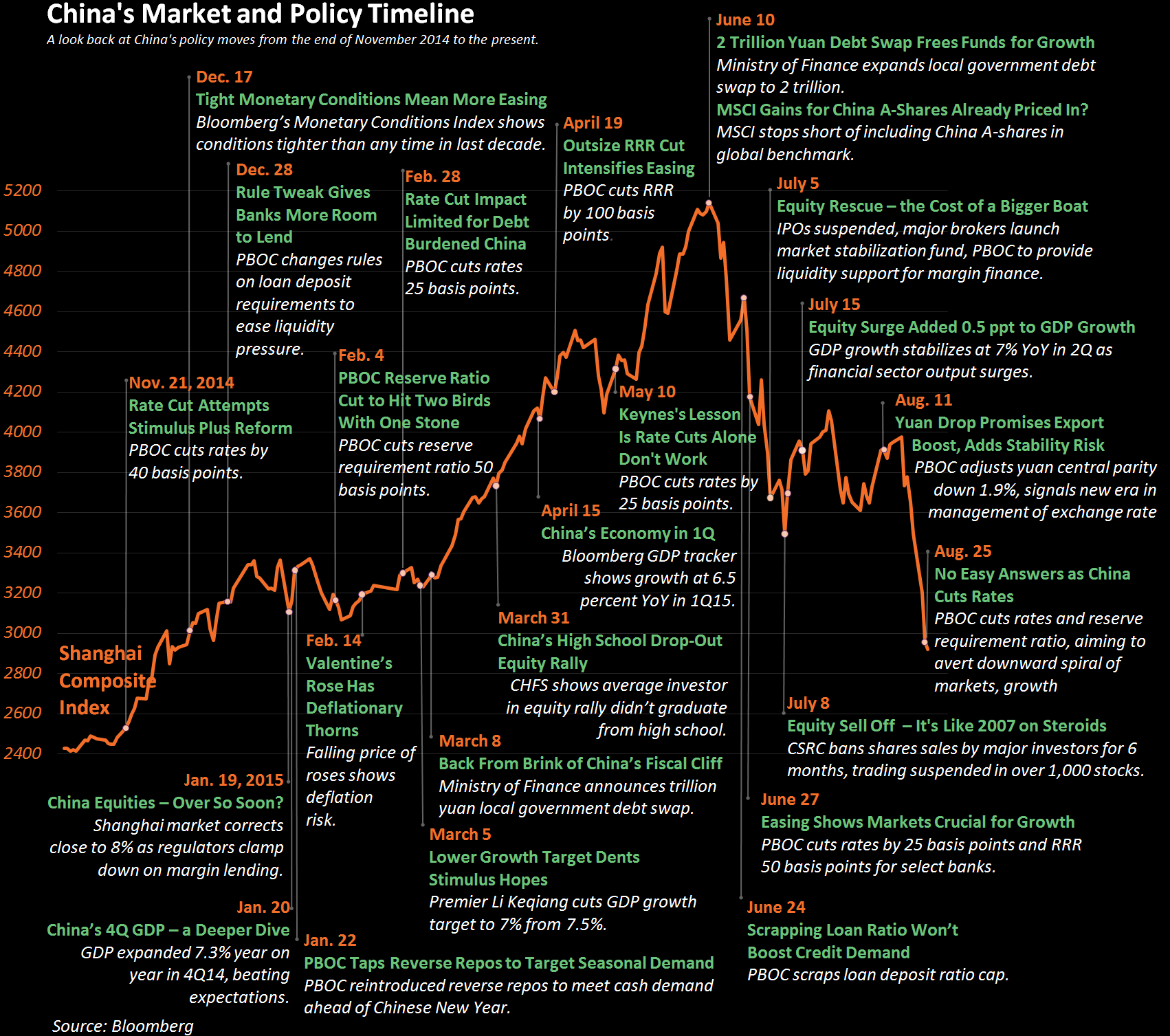

The China Story is Over

And I don’t mean the high growth forever fantasy tale, I mean the entire China narrative is over:

- That export-dependent China can seamlessly transition to a self-supporting consumer economy.

- That China can become a value story now that the growth story is done.

- That central planning will ably guide the Chinese economy through every rough patch.

- That corruption is being excised from the system.

- That the asset bubbles inflated by a quadrupling of debt from $7 trillion in 2007 to $28 trillion can all be deflated without harming the wealth effect or future debt expansion.

- That development-dependent local governments will effortlessly find new funding sources when land development slows.

- That workers displaced by declining exports and automation will quickly find high-paying employment elsewhere in the economy.

I could go on, but you get the point: the entire Story is over. (I explained why in a previous essay, Is China’s “Black Box” Economy About to Come Apart? )

This is entirely predictable. Every fast-growing economy starting with near-zero debt and huge untapped reserves of cheap labor experiences an explosive rise as the low-hanging fruit is plucked and the same abrupt stall and stagnation when the low-hanging fruit has all been harvested, leaving only the unavoidable results of debt-fueled speculation: an enormous overhang of bad debt, malinvestment (a.k.a. bridges to nowhere and ghost cities) and policies that seemed brilliant in the good old days that are now yielding negative returns.

The Emerging Market Story Is Also Done

Emerging currencies and markets have soared on the back of the China Story, as China’s insatiable demand for oil, iron ore, copper, soy beans, etc. drove global demand to unparalleled heights.

This demand pushed prices higher, which then pushed production (supply) higher, as the low cost of capital globally enabled marginal resources to be put into production with borrowed money.

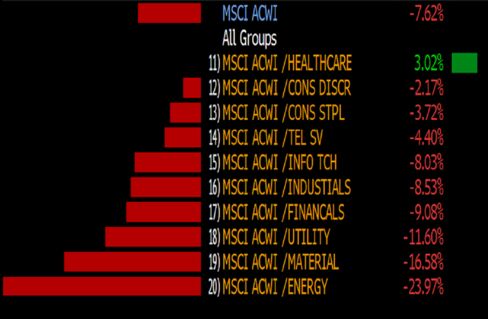

Now that China’s demand has fallen off—by some accounts, China’s GDP is actually in negative territory, despite official claims that it’s still growing at 7% annually—commodity prices have crashed, taking the emerging markets’ stock and currency markets down. (Source)

Here is a chart of Doctor Copper, a bellwether for industrial and construction demand:

Here is Brazil’s stock market, which has declined 54% in the past 12 months:

These are catastrophic declines, and with China’s growth story over, there is absolutely nothing on the global horizon to push demand back up.

Diminishing Returns on Additional Debt

The simple truth is that expanding debt has fueled global growth. Though people identify China as the driver of global demand for commodities, China’s growth is debt-driven. As noted above, China quadrupled its officially tracked debt from $7 trillion in 2007 to $28 trillion as of mid-2014—an astonishing 282 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). If we add the estimated $5 trillion of shadow-banking system debt and another year’s expansion of borrowing, China’s total debt of $35+ trillion is in excess of 300% of GDP—levels associated with doomed to default states such as Greece and Spain.

While China has moved to open the debt spigot in recent days by lowering interest rates and reserve requirements, this doesn’t make over-indebted borrowers good credit risks or more empty high-rises productive investments.

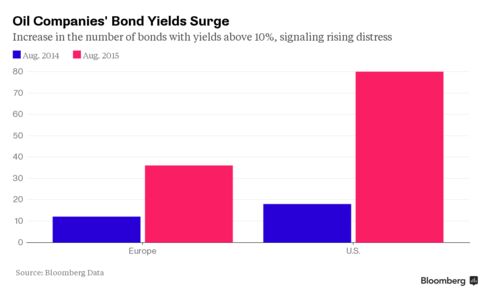

Borrowed money that poured into ramping up production in emerging nations is now stranded as prices have plummeted, rendering marginal production intensely unprofitable.

In sum: greatly expanding debt boosted growth virtually everywhere after the Global Financial Meltdown of 2008-2009. That fix is a one-off: not even China can quadruple its $35+ trillion debt to $140 trillion to reignite growth.

Here is a sobering chart of global debt growth:

Limits on Deficit-Spending (Borrowed) Fiscal Stimulus

When the global economy rolled over into recession in 2008, governments borrowed money by selling sovereign bonds to fund increased state spending. In the U.S., federal borrowing soared to over $1 trillion per year as the government sought to replace declining private spending with public spending.

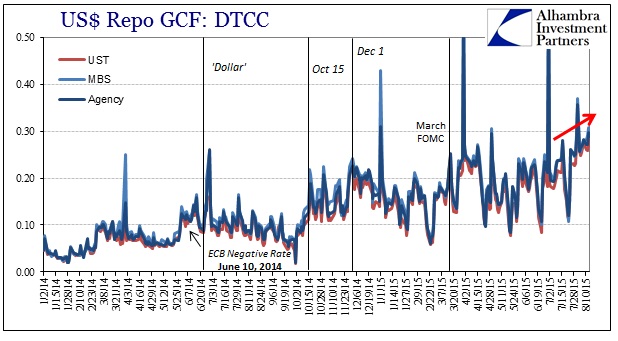

Governments around the world have continued to run large deficits, piling up immense debts since 2008. The global move to near-zero yields has enabled governments to support these monumental debt loads, but even at near-zero yields, the interest payments are non-trivial. These enormous sovereign debts place some limits on how much governments can borrow in the next global recession—a slowdown many think has already started.

Here is a chart of U.S. sovereign debt, which has almost doubled since 2008:

As noted on the chart: what structural inadequacies or problems did governments fix by borrowing gargantuan sums to fund state spending? The basic answer is: none. All the same structural problems facing governments in 2008 remain untouched in 2015. These include: over-indebtedness, bad debts that haven’t been written down, insolvent banks, soaring social spending as the worker-retiree ratio slips below 2-to-1, externalized environmental damage that has yet to be remediated, and so on.

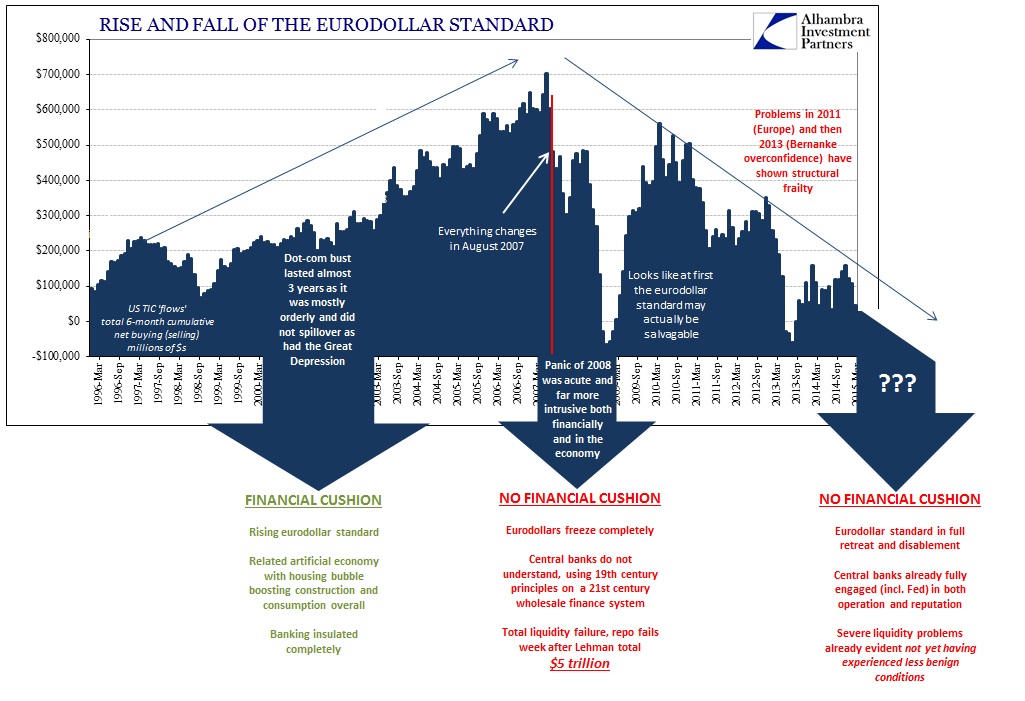

Central Bank Stimulus (Quantitative Easing) as Social Policy Has Been Discredited

In the wake of the Global Financial Meltdown of 2008-2009, central banks launched monetary stimulus programs aimed at pumping money into the economy via bank lending. The stated goals of these stimulus programs were 1) boost employment (i.e. lower unemployment) and 2) generate enough inflation to stave off deflation, which is generally viewed as the cause of financial depressions.

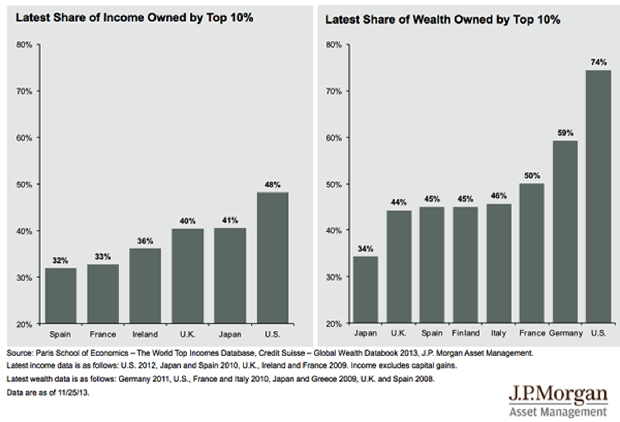

While it can be argued that these unprecedented monetary stimulus programs achieved modest successes in terms of lowering unemployment and pushing inflation above the zero line, they also widened wealth and income inequality.

Even as these programs made modest dents in unemployment and deflation, they pushed asset valuations to the moon—assets largely owned by the few at the top of the wealth pyramid.

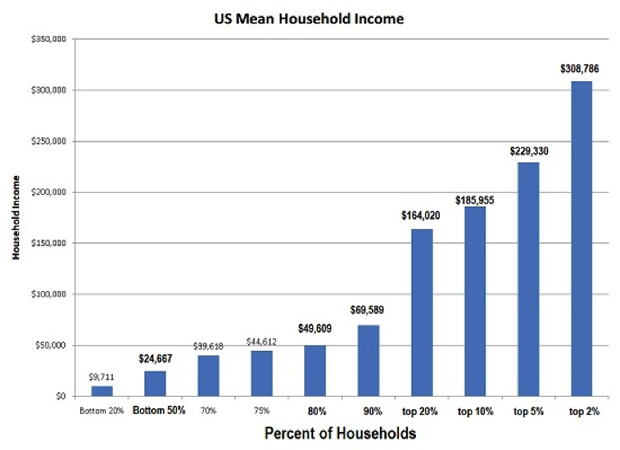

Here is a chart of selected developed economies’ income/wealth skew:

The widespread recognition that the benefits of central bank stimulus mostly flowed to the top of the pyramid places political limits on future central bank stimulus programs.

The 2008-09 Fixes Are No Longer Available

In summary, the fixes for the 2008-09 recession are no longer available in the same scale or effectiveness. Expanding debt to push up demand and investment, rising state deficit spending, massive monetary stimulus programs—all of these now face limitations. This means the central banks and states have very limited tools to reignite growth as global recession trims borrowing, investment, hiring, sales and profits.

Related Posts

- 77The yuan will be able to trade as much as 2% on either side of a daily central bank reference rate, compared with the current 1%

- 76China's central bank is prepared to take its strongest action since 2012 to loosen monetary policy if economic growth slows further, by cutting the amount of cash that banks must keep as reserves, sources involved in internal policy discussions say. A cut would be triggered if growth slips below 7.5…

- 69China's central bank reiterated its stance of continuing with a stable monetary policy this year and promising to contain risks in lending, noting that the economy has yet to find a stable base for growth. In its quarterly monetary policy report, released on Saturday, the People's Bank of China (PBOC)…

- 66When the banking crisis crippled global markets seven years ago, central bankers stepped in as lenders of last resort. Profligate private-sector loans were moved on to the public-sector balance sheet and vast money-printing gave the global economy room to heal. Time is now rapidly running out. From China to…

- 63(Source http://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/comment/david-blanchflower/david-blanchflower-we-should-fear-deflation--not-welcome-it-9986726.html ) The UK isn’t in deflation yet. While central bankers know what to do about stopping inflation, they don’t know what to do about halting deflation. The Swiss National Bank last week abandoned its attempt to defend a currency floor, which caused a sharp appreciation in its currency, which…